The EU and Belarus Engaged - No Wedding in Sight

Rácz, AndrásDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (1.089 KB)

| URL | https://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/3206/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 101 |

| ISBN: | 978-3-942532-17-4 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2010 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 23.10.2011 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/downloads/prif101.pdf (2010) |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | Europäische Union , Weißrussland , Kooperation |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.73 (Europapolitik, Europäische Union), 89.90 (Außenpolitik, Internationale Politik) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

Almost exactly four years ago, on 21 November 2006, the European Commission released a so-called non-paper entitled “What the EU could bring to Belarus” In this document, the EU offered Belarus several political, technical and infrastructural possibilities for cooperation, under the condition that Minsk improves the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to free and fair elections and free media. An overview of the last four years of the EU-Belarus relationship is more than relevant today, coming as it does shortly after the presidential elections in Belarus – which has been rescheduled to take place on 19 December 2010, earlier than the regular date – and four years after the release of the non-paper. It is a well known fact that the relationship with the EU is not of primary importance for the Minsk leadership, but is regarded rather as a political tool to counter-balance the overwhelming influence of Russia. The Russian factor not only affects the foreign and security policy of Belarus, but also has a decisive influence on its foreign trade patterns. In other words, the shift in Belarusian foreign policy in a more pro-EU direction, which has been taking place since 2007, is connected with the changing attitude of Russia towards Belarus, and is not an indigenous, domestically motivated move. However, the Belarusian leadership has always been reluctant to commit itself too much to the EU, especially when it comes to democratic values. Instead, Minsk has been striving to narrow EU-Belarus relations down to cooperation on foreign trade, investments, infrastructure, visa issues, etc. – in other words, primarily to technical issues. Taking into account the EU’s intentions as described in the non-paper, this strategy of managing EU-Belarus relations over the last 4 to 5 years has been largely, though not fully successful from the perspective of the Belarusian regime. On the one hand, the relationship with the EU has clearly improved in recent years: Belarus was included in the Eastern Partnership initiative, the visa ban on Belarusian leaders was by and large suspended, investments from the EU are growing, foreign trade is intensifying, more and more new loans are being received from the West etc. On the other hand, the regime has managed to avoid introducing any significant reforms that would have affected the core structures of the political system in terms of democratic and human rights and fundamental freedoms. Despite the EU’s increasing engagement towards Belarus, the nature of the regime has practically remained the same since the last presidential elections in 2006. The lack of significant changes in this field can easily be confirmed by using quantitative indicators such as the Democracy Index of the Economist Intelligence Unit, or the “Freedom in the World” indicator compiled by Freedom House. Studying quantitative indicators might well lead to the conclusion that the EU’s policy towards Belarus has seemingly failed in terms of protecting and fostering human rights and civil freedoms. This as well demonstrated by the brutal suppression of the opposition demonstration following the 19 December 2010 election. However, other quantitative sources, such as the Index of Economic Freedom of the Heritage Foundation and various indicators of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development show that the regime has actually changed in recent years to a quite significant extent in terms of economic freedoms such as banking, privatization, trade and investment policy etc. The motivation for such changes is connected to the fact that sustaining social stability is of crucial importance for the Belarusian leadership. Social stability is the factor which has ensured strong domestic support for the Lukashenko system over the last decade. Minsk has been in growing need of external sources of funding since the oil and gas price war on the eve of 2006/2007. The government introduced several measures to intensify foreign trade and attract more investments, and to obtain more and more external loans and credits. The paper argues that more emphasis should be put on economic transformation within the framework of the conditionality approach of the EU. The main reason for this is that the Lukashenko regime has shown practically no signs of cooperation in terms of human rights and fundamental freedoms. The policy of the regime has remained largely unchanged in these areas over the last four years. On the other hand, Minsk has already conducted a number of significant economic reforms, and others are on the way. The government had the best motivation to do so: by liberalizing the national economy it intends to counter-balance the growing influence of Russia and maintain the level of social stability that guarantees the regime’s domestic legitimacy. Belarus is striving to attract Western investors, obtain loans, and increase incomes by privatizing certain elements of the still largely state-dominated national economy. All in all, while the regime is not at all cooperative in terms of human rights, there is a definite readiness for reforms in the field of the economy. Consequently, fostering economic transformation could be the main entry point for the EU’s foreign policy towards Belarus. Focusing on the economy relations would also allow the EU to introduce such sanctions against the Lukashenko regime that would be much more painful, than the ones adopted on 31 January 2011. Indeed, economy is the point, where the EU could motivate Belarus, either in a positive way (by supporting economic reforms), or in a negative way (by introducing economic sanctions that would cause immediate and serious losses of incomes). The human rights dialogue should, of course, not be abandoned, since protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms is a core value of the European Union as a whole, including its Neighbourhood Policy. This is particularly necessary following the 19 December 2010 events. However, strategic efforts should be concentrated more on the broader economic sphere. All in all, conditionality has not failed as a strategy towards Belarus, but should become more balanced. Instead of a solely human rights and democracy-dominated approach, in the long run EU conditionality should focus also on economic and administrative aspects. Such a shift could be applied also if the EU decides to introduce additional, stronger sanctions. All in all, also economic tools should be used for protecting human rights.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

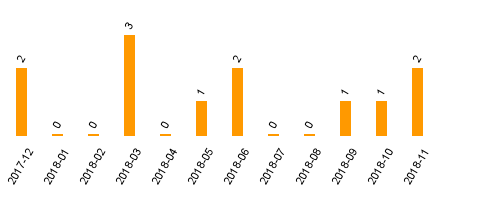

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)