Militarized versus Civilian Policing : Problems of Reforming the Afghan National Police

Friesendorf, CorneliusDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (1.045 KB)

| URL | https://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/3207/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 102 |

| ISBN: | 978-3-942532-18-1 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2011 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 23.10.2011 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/downloads/prif102.pdf (2011) |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | Afghanistan , Polizei , Reform |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 88.17 (Ordnungskräfte), 89.99 (Politologie: Sonstiges) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

It is difficult to establish the right relationship between military and civilian elements when reforming the police forces in conflict and post-conflict regions. Principles of civilian and democratic Security Sector Reform (SSR) emphasize the need to separate the military and the police. Nevertheless, everyday reality in many places does not allow the realization of this ideal type. The police must adopt a robust stance in order to close security gaps and proceed against well organized armed criminals or insurgents. In the context of police-building and police reform in fragile states, this means that the police must be as civilian as possible and as military as necessary – with regard to their equipment, approach, structure and duties. The rapid militarization of the police can cause problems. It can lead to a rift between the police and the public which prevents the development of a relationship of trust that is so important for police work. External actors in Afghanistan are in the process of transferring the responsibility for security to Afghan institutions. By the end of 2014, the Afghan security forces are to combat insurgency and protect the state and its citizens. Donors are therefore investing huge sums, not only in training and equipping the Afghan National Army (ANA), but also in building the Afghan National Police (ANP). This report studies the transition from civilian to military-dominated police-building in Afghanistan. From 2002, Germany was the lead nation responsible for coordinating international assistance for police-building. The German police programme in Afghanistan was designed as a sustainable project with a civilian approach. However, Germany only invested relatively little funds in the building and reform of the ANP. This reflected the initially rather limited involvement of the international community as a whole in Afghanistan. The United States’ Afghanistan policy relied on cooperation with the warlords as well as on the military regime in Pakistan. This policy served to strengthen the armed opposition forces. Once it became clear that the building of the ANP was not progressing quickly enough, the USA de facto assumed the lead role in police-building in Afghanistan. This meant a change of paradigm from a civilian-based police reform to a military-based police reform. Militarization was accelerated by the USdominated change of strategy in favour of counterinsurgency in 2009. The report refers to the problems of the dominance of military elements in building the ANP. It is not clear whether the militarization of the ANP has significantly improved the chances of survival for members of the Afghan police. What is certain is that militarization cannot solve the problem of the weak legitimacy of the Afghan state. There is still a lack of trust between the public and the police, especially as the ANP is inadequately equipped to prevent or solve crimes. Moreover, the possible long-term consequences of militarization are problematic: It is easier to militarize the police now than it will be to drive out the spirit of militarization at a later date. The militarization of the ANP is therefore at the best ineffective and at the worst counterproductive. Only a police force which the people trust can be effective. Apart from describing the shift away from a civilian police model and studying the reasons for this transition, the report also has a normative aim: It emphasizes the need for advancing civilian police-building. The preconditions for this in Afghanistan are everything but ideal. The argument that police reform – and SSR in general – must take second place to strengthening the ANP is wrong, however. After all, it was precisely the neglect of police reform that contributed to the deterioration of the security situation in the first place. Police reform can only be sustainable if it is linked to reforms in police administrative structures and supervisory authorities. The rapid, militarized build-up of the police can only create stability in the short term, if at all. The regular police force – the Afghan Uniformed Civilian Police (AUCP) – should concentrate on preventing and solving crime. Admittedly, in Afghanistan this calls for certain military elements in training and equipment so that the police are able to protect themselves from attacks. However, only an understanding of civilian police work can establish an atmosphere of trust between the public and the police. Various steps are necessary to realign police reform in Afghanistan. Civilian police experts, not soldiers, should dominate the strategic approach to police reform. Furthermore, measures must be taken to tackle the shortage of civilian instructors, partners and mentors as quickly as possible. It is also important to support the ANP in the long term. The two to three-year project cycles that are normal for international cooperation are usually not sufficient for sustainable police reform, among other things because they do not give local stakeholders sufficient planning security. Many further steps are necessary to improve police work in Afghanistan. These include the reform of the Ministry of Interior Affairs, the clear demarcation of areas of responsibility vis-à-vis other security players, and closer intermeshing with the justice sector. Furthermore, the difficult balancing act between (military) self-defence and the openness of the police towards the public requires regional adjustments. These must be accompanied by training contents and police work that are in touch with the people, as well as by literacy campaigns. This report does not call for a new police strategy but for a gradual realignment of the reform of the Afghan police that will serve the needs of the Afghan people better than efforts to militarize the police.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

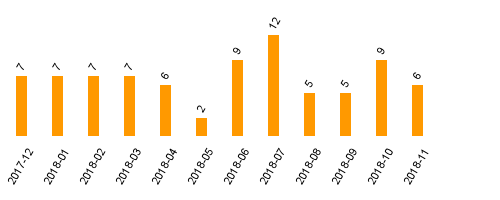

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)