Unilateral strains on transatlantic relations : US sanctions against those who trade with Cuba, Iran, and Libya, and their effects on the world trade regime

Gerke, KinkaDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (20 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2008/285/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 47 |

| Sprache: | Deutsch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 1997 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 31.01.2008 |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | USA , Wirtschaftssanktion , Kuba , Iran , Libyen |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.90 (Außenpolitik, Internationale Politik) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

In 1996, within the space of a mere five months, the American Congress passed two laws which tightened up the USA's economic embargo against Cuba, Iran, and Libya. The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act and the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act also provide for sanctions against firms and persons from third countries who refuse to fall into line with the stricter American sanctions regulations. By threatening to impose these kinds of secondary sanctions, the USA is seeking to get its laws and policies enforced outside as well as inside its own territory, and to force others—first and foremost its allies—to toe the line against their will: they are being presented with the alternative of maintaining economic relations either with the USA or with those countries against which America has instituted sanctions. In acting in this way, the USA is violating both international law and some of the central rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Underlying the dispute is a clash of views about how to deal with totalitarian regimes. Whilst the Europeans share the United States' political goals, they contest the American view that political and economic isolation is the appropriate means to achieve them. The United States thus once again succumbed to the temptation of unilateralism—not because, as the last remaining superpower, it is suffering from hubris, but because the structural changes in the international system have caused the inherent dominance of domestic politics in the USA to make itself felt more strongly. The two sanctions acts are thus not electorally determined 'slip-ups', but an expression of the greater importance of domestic politics in the formulation of foreign policy. At the same time, they signal that the USA has become less predictable as a leading power. The American election, which played a crucial role in the adoption of secondary sanctions, merely reinforced the existing trends, because it enabled interest groups to exert a disproportionate influence on the foreign-policy decision-making process. The initiative for the imposition of secondary sanctions came from Congress. The latter's changed role in the USA's foreign-policy decision-making process, and its changed composition, played a major part. Its influence on the formulation of foreign policy has increased with the ending of the Cold War, it has assumed a more active role in foreign policy and is demanding to have its say. Since it traditionally gears its decision more to internal political requirements and particular interests, the chances of well-organized interest-groups to exert an influence have increased, and local considerations have acquired greater significance. The trend towards a more strongly domestically determined foreign policy was reinforced by the 'conservative revolution' in Congress in 1994. It increased the number of those who rejected multilateralism and international co-operation and placed their trust in unilateral solutions and emphasis on American military strength —a trend which continued with the 1996 elections. It is therefore likely that in future, internal politics will be given greater weight. The coming-into-force of the law was made possible by a president faced with the question of whether he should promote observance of international law and regime rules, or should give priority to the satisfaction of particular internal political interests, in order not to endanger his chances of re-election. He opted for the latter and refrained from using his veto. He did this even though he was against the use of secondary sanctions as a means of enforcing American policy and was aware that in using them the USA was in flagrant violation of international law and the rules of the world trade regime. Clinton thus failed to fulfil his constitutional tasks of providing a counterweight to, and controlling authority for, the often very locally oriented decisions of Congress, of taking account of the national interest, and of ensuring observance of international contractual obligations and international law. Finally, the secondary sanctions are a reflection of the USA's decreased political scope for action, which has boosted the importance of symbolic politics. The imposition of sanctions suggests resolve and strength and thus reduces the political costs of non-action — which is why it has been a favourite device of all presidents. This is especially true in situations where the threat posed by the opponent has previously been overdramatized. Furthermore, sanctions appear cheap in internal political terms, because the costs in external political and external economic terms (where counter-measures are taken) are only seen and felt in the longer term. But their increasing popularity is also an effect of declining external political budgets, which debar the USA from other options for action. It is therefore likely that the importance of sanctions in the USA's external political arsenal will not diminish but increase. And yet there are important differences between the two sanctions acts. The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act (Helms-Burton Act) is primarily the product of the influence of a small extreme right-wing group of Cuban exiles and of President Clinton's conceding against his better judgement. By means of this act, the Cuban exiles managed not only to tighten up and codify the US economic embargo that had been in force since 1962, but also to curtail the president's competencies in foreign affairs. At the same time, the present analysis shows that the act's provisions are not appropriate for achieving the democratization of Cuba which the authors of the act claimed was their objective. In the case of Iran, on the other hand, the USA found itself in a structural dilemma. It had the legitimate goal of wanting to deprive the country of the means to expand its military power and strength, which constituted a security risk; but it could not fulfil this goal without its allies' co-operation, and this they refused to give. However, it is not only the USA, but the whole international community, that is confronted with the problem of how Iran might be persuaded to change its policy. Up to now, it is clear that neither the strategy of containment and complete isolation of the country, nor the 'critical dialogue' pursued by the Europeans has been a success. It is therefore time that both sides showed a willingness to enter into dialogue and to try jointly to work out an alternative strategy. The fact that the US administration, out of internal political and electoral calculations, is abandoning central principles of its foreign policy, violating international rules, and ignoring the interests of its European allies, raises the question of the reliability of the USA as a leading world power and as guarantor of the world order and the international regimes which it has itself created. For the Europeans, the question arises as to how—without jeopardizing the existence of the regime by their own actions— they should deal with a leading power that has become less predictable, violates the rules of the regime, and itself puts the regime at risk? The EU has lodged a complaint against the Helms-Burton Act with the World Trade Organization (WTO). Like Canada and Mexico, it sees the act as a violation of the provisions of the 1993 Uruguay Round agreement. The USA does not deny that its action violates the rules of the world trade regime; but it seeks to justify the violation by reference to a GATT exception clause designed "to preserve national security"'— a clause that has been invoked only in exceptional cases throughout GATT's history. Whereas a GATT panel previously ruled that secondary sanctions were not in accord with the rules of the trade regime, there has hitherto never been a ruling as to whether an invocation of this clause was warranted or not. Yet, because of the changes in the dispute-settlement procedure and the short time which the WTO as a new organization has had to prove itself in the eyes of its opponents in the USA, the European complaint to the WTO harbours a great political danger as regards the continued existence of the regime, and support for it in the USA. Should the panel decide that secondary embargoes are not covered by the GATT security clause, and thus contravene GATT, it risks its judgement being interpreted and represented by the USA's opponents in a way that implies that the GATT rules prohibit the USA from defending its security interests. This could do great damage to the fragile consensus which the newly created WTO enjoys in the USA. The credibility of the WTO in the USA would then, in certain circumstances, be discredited even before it had had an opportunity to prove the fairness of the new procedure. In the worst case, this would cause a 'backlash' in Congress and lead to America's membership of the WTO being called into question. Should the panel decide that the secondary sanctions are in accordance with the rules of the trade regime, this too would be deleterious to the regime. The floodgates would be opened for a general invocation of the security clause. Smaller member-states in particular would view this as an abuse of power by the USA, and the operation of the trade regime as a strong rule-oriented and power-oriented regulatory instrument would be placed in doubt. Whilst the European complaint threatened to land the WTO between Scylla and Charybdis, the US declaration that the WTO has no competence to judge this question and its announcement to boycott the panel procedure not only challenged the right of the WTO to judge complaints. It also undermined the authority of the organization and its mechanism to settle disputes, the main tool for enforcing trade rules. The compromise that was struck in April 1997 does not solve the conflict, it merely averts the immediate threat of a further escalation of the conflict. The damage to the reputation of the WTO is nevertheless done. The Europeans should avoid to push its complaint to the WTO further, because the risk associated with the complaint is too great for the regime. Instead, they should stick to effective counter-measures such as the anti-boycott legislation, because they raise the costs of illicit behaviour for the USA. Such measures are also an effective means of mobilizing American economic opposition. Pressure from the US business community is the best means of persuading Congress to lift or revoke the sanctions laws and to be dissuade to use secondary sanctions as a means for promoting its foreign policy goal. In addition, the Europeans should seek to exert greater influence on the internal political decision-making process in the USA, by making it clear to the decision-makers that upholding the trade regime and respecting its rules is in the USA's own interests. In 1996, within the space of a mere five months, the American Congress passed two laws which tightened up the USA's economic embargo against Cuba, Iran, and Libya. The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act and the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act also provide for sanctions against firms and persons from third countries who refuse to fall into line with the stricter American sanctions regulations. By threatening to impose these kinds of secondary sanctions, the USA is seeking to get its laws and policies enforced outside as well as inside its own territory, and to force others—first and foremost its allies—to toe the line against their will: they are being presented with the alternative of maintaining economic relations either with the USA or with those countries against which America has instituted sanctions. In acting in this way, the USA is violating both international law and some of the central rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Underlying the dispute is a clash of views about how to deal with totalitarian regimes. Whilst the Europeans share the United States' political goals, they contest the American view that political and economic isolation is the appropriate means to achieve them. The United States thus once again succumbed to the temptation of unilateralism—not because, as the last remaining superpower, it is suffering from hubris, but because the structural changes in the international system have caused the inherent dominance of domestic politics in the USA to make itself felt more strongly. The two sanctions acts are thus not electorally determined 'slip-ups', but an expression of the greater importance of domestic politics in the formulation of foreign policy. At the same time, they signal that the USA has become less predictable as a leading power. The American election, which played a crucial role in the adoption of secondary sanctions, merely reinforced the existing trends, because it enabled interest groups to exert a disproportionate influence on the foreign-policy decision-making process. The initiative for the imposition of secondary sanctions came from Congress. The latter's changed role in the USA's foreign-policy decision-making process, and its changed composition, played a major part. Its influence on the formulation of foreign policy has increased with the ending of the Cold War, it has assumed a more active role in foreign policy and is demanding to have its say. Since it traditionally gears its decision more to internal political requirements and particular interests, the chances of well-organized interest-groups to exert an influence have increased, and local considerations have acquired greater significance. The trend towards a more strongly domestically determined foreign policy was reinforced by the 'conservative revolution' in Congress in 1994. It increased the number of those who rejected multilateralism and international co-operation and placed their trust in unilateral solutions and emphasis on American military strength —a trend which continued with the 1996 elections. It is therefore likely that in future, internal politics will be given greater weight. The coming-into-force of the law was made possible by a president faced with the question of whether he should promote observance of international law and regime rules, or should give priority to the satisfaction of particular internal political interests, in order not to endanger his chances of re-election. He opted for the latter and refrained from using his veto. He did this even though he was against the use of secondary sanctions as a means of enforcing American policy and was aware that in using them the USA was in flagrant violation of international law and the rules of the world trade regime. Clinton thus failed to fulfil his constitutional tasks of providing a counterweight to, and controlling authority for, the often very locally oriented decisions of Congress, of taking account of the national interest, and of ensuring observance of international contractual obligations and international law. Finally, the secondary sanctions are a reflection of the USA's decreased political scope for action, which has boosted the importance of symbolic politics. The imposition of sanctions suggests resolve and strength and thus reduces the political costs of non-action — which is why it has been a favourite device of all presidents. This is especially true in situations where the threat posed by the opponent has previously been overdramatized. Furthermore, sanctions appear cheap in internal political terms, because the costs in external political and external economic terms (where counter-measures are taken) are only seen and felt in the longer term. But their increasing popularity is also an effect of declining external political budgets, which debar the USA from other options for action. It is therefore likely that the importance of sanctions in the USA's external political arsenal will not diminish but increase. And yet there are important differences between the two sanctions acts. The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act (Helms-Burton Act) is primarily the product of the influence of a small extreme right-wing group of Cuban exiles and of President Clinton's conceding against his better judgement. By means of this act, the Cuban exiles managed not only to tighten up and codify the US economic embargo that had been in force since 1962, but also to curtail the president's competencies in foreign affairs. At the same time, the present analysis shows that the act's provisions are not appropriate for achieving the democratization of Cuba which the authors of the act claimed was their objective. In the case of Iran, on the other hand, the USA found itself in a structural dilemma. It had the legitimate goal of wanting to deprive the country of the means to expand its military power and strength, which constituted a security risk; but it could not fulfil this goal without its allies' co-operation, and this they refused to give. However, it is not only the USA, but the whole international community, that is confronted with the problem of how Iran might be persuaded to change its policy. Up to now, it is clear that neither the strategy of containment and complete isolation of the country, nor the 'critical dialogue' pursued by the Europeans has been a success. It is therefore time that both sides showed a willingness to enter into dialogue and to try jointly to work out an alternative strategy. The fact that the US administration, out of internal political and electoral calculations, is abandoning central principles of its foreign policy, violating international rules, and ignoring the interests of its European allies, raises the question of the reliability of the USA as a leading world power and as guarantor of the world order and the international regimes which it has itself created. For the Europeans, the question arises as to how—without jeopardizing the existence of the regime by their own actions— they should deal with a leading power that has become less predictable, violates the rules of the regime, and itself puts the regime at risk? The EU has lodged a complaint against the Helms-Burton Act with the World Trade Organization (WTO). Like Canada and Mexico, it sees the act as a violation of the provisions of the 1993 Uruguay Round agreement. The USA does not deny that its action violates the rules of the world trade regime; but it seeks to justify the violation by reference to a GATT exception clause designed "to preserve national security"'— a clause that has been invoked only in exceptional cases throughout GATT's history. Whereas a GATT panel previously ruled that secondary sanctions were not in accord with the rules of the trade regime, there has hitherto never been a ruling as to whether an invocation of this clause was warranted or not. Yet, because of the changes in the dispute-settlement procedure and the short time which the WTO as a new organization has had to prove itself in the eyes of its opponents in the USA, the European complaint to the WTO harbours a great political danger as regards the continued existence of the regime, and support for it in the USA. Should the panel decide that secondary embargoes are not covered by the GATT security clause, and thus contravene GATT, it risks its judgement being interpreted and represented by the USA's opponents in a way that implies that the GATT rules prohibit the USA from defending its security interests. This could do great damage to the fragile consensus which the newly created WTO enjoys in the USA. The credibility of the WTO in the USA would then, in certain circumstances, be discredited even before it had had an opportunity to prove the fairness of the new procedure. In the worst case, this would cause a 'backlash' in Congress and lead to America's membership of the WTO being called into question. Should the panel decide that the secondary sanctions are in accordance with the rules of the trade regime, this too would be deleterious to the regime. The floodgates would be opened for a general invocation of the security clause. Smaller member-states in particular would view this as an abuse of power by the USA, and the operation of the trade regime as a strong rule-oriented and power-oriented regulatory instrument would be placed in doubt. Whilst the European complaint threatened to land the WTO between Scylla and Charybdis, the US declaration that the WTO has no competence to judge this question and its announcement to boycott the panel procedure not only challenged the right of the WTO to judge complaints. It also undermined the authority of the organization and its mechanism to settle disputes, the main tool for enforcing trade rules. The compromise that was struck in April 1997 does not solve the conflict, it merely averts the immediate threat of a further escalation of the conflict. The damage to the reputation of the WTO is nevertheless done. The Europeans should avoid to push its complaint to the WTO further, because the risk associated with the complaint is too great for the regime. Instead, they should stick to effective counter-measures such as the anti-boycott legislation, because they raise the costs of illicit behaviour for the USA. Such measures are also an effective means of mobilizing American economic opposition. Pressure from the US business community is the best means of persuading Congress to lift or revoke the sanctions laws and to be dissuade to use secondary sanctions as a means for promoting its foreign policy goal. In addition, the Europeans should seek to exert greater influence on the internal political decision-making process in the USA, by making it clear to the decision-makers that upholding the trade regime and respecting its rules is in the USA's own interests.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

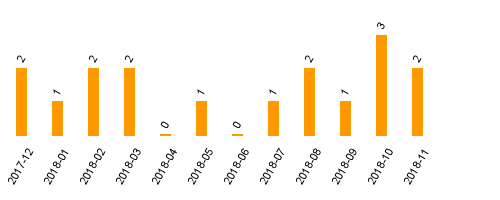

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)