Farewell Non-Alignment? Constancy and change of foreign policy in post-colonial India

Rauch, CarstenWeitere beteiligte Personen: Hughes, Katharine (Übersetzer) ; Peace Research Institute Frankfurt

Download:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (993 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2009/1164/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 85 |

| ISBN: | 978-3-937829-73-9 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2008 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 02.04.2009 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/downloads/prif85.pdf (2008) |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.76 (Friedensforschung, Konfliktforschung) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

In 1947 India, formerly a colony of the British Empire, became independent. In 1974 it detonated its first nuclear device. However, it is only in the last few years that the country with the world’s second largest population has been recognised as a potential future world power. Since its economy opened up in 1990, India has been achieving fantastic growth and is experiencing a boom only exceeded by that of China. In view of these facts, the way this Asian giant with its increased weight directs its foreign policy is of exceptional importance. One possible response to this would be to expect constancy of India’s foreign policy. After all, the concept of non-alignment, developed by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, continues to be featured in almost all keynote addresses by politicians of every hue and is still thought of (as it has been for the last 60 years) as a central tenet of India’s foreign policy. On the other hand, the transformation which shifting parameters almost inevitably had to involve could also be emphasized. After all, there are one or two things which have changed in the India of 2008 since the India of the middle of the last century or the India at the height of the Cold War. In terms of domestic policy, the end of the domination of the once unchallenged Indian National Congress, or Congress Party, ought to be mentioned. Until 1990, almost without a break, this party was part of, or entirely constituted, the government. Since then this domination has come to an end: a second party with a similar level of influence at national level has arisen in the form of the BJP. Both are nonetheless considerably weaker than the Congress Party in its heyday, and are therefore dependent on numerous coalition partners. Furthermore, the Indian electorate has become more critical and since 1989, with one exception, has sent the current government into opposition at every national parliamentary election. The reform of the economic system, which used to be closed and quasi-socialist, likewise falls in the realm of domestic policy. This successfully broke with old dogmas and, having since become a cross-party consensus, is no longer endangered by a change of government. In terms of foreign policy, more than anything else the end of the Cold War completely overturned the parameters of India’s foreign policy: the Soviet Union, a good friend and since 1972 to all intents and purposes an alliance partner, suddenly no longer existed, and on the other side of the coin one or two impediments to cooperation, which had formerly substantially hindered relations with the USA, ceased to apply. From this one or two observers derive the diagnosis, referred to in this report as the Farewell Non-alignment Hypothesis, that since the end of the Cold War India has – under the influence of an increasingly neo-liberal economy and under pressure from the superpower USA – distanced itself (too) far from the once cherished ideal of a non-aligned, moral foreign policy rooted in peaceful cooperation. The conclusions of this report however suggest a different point of view. An analysis of India’s foreign policy since 1947 in the subject areas of world and regional policy produces the following results: 1. It makes sense to differentiate three phases of India’s foreign policy during this period (1947-1965, 1966-1989 and 1990-present). While these are far from being completely homogeneous in themselves, they do plainly differ from one another with regard to the relevant protagonists at work, the contexts of foreign and domestic policy, and the actual output in terms of foreign policy. 2. There is no evidence in any of these three phases of irreproachable adherence to the principles of non-alignment. Not only after the end of the Cold War, as the Farewell Non-alignment Hypothesis suggests, but already under Indira Gandhi and even as early as under Jawaharlal Nehru there are numerous examples to be found of divergences from this ideal. 3. The overridingly important goal in all three phases was (and is) to preserve India’s independence and ability to act, to maximize Indian possibilities for influence and, put in quite general terms, to make India into a Global Player, with a voice which will command attention in the shaping of world order. 4. As long as India was extremely weak, non-alignment and involvement in the Nonaligned Movement were perceived in New Delhi as an ideal vehicle for drawing nearer to these goals. However, the stronger India becomes, the more any involvement in this movement loses its attraction. 5. A further change in India’s orientation, for instance a closer cooperation with the People’s Republic of China, cannot therefore be ruled out in the future, if India’s leadership has the impression that by so doing it is able to draw nearer to the interests already outlined. 6. The way in which democracy has in the mean time become firmly anchored in the Indian system of values, and the way earlier impediments to cooperation have been put aside nonetheless give rise to the hope that India’s turn towards the west may last for some considerable time. In contrast to the USA, which used the end of the Cold War to put its relations with India onto a whole new level, Germany and the EU have so far largely slept through this development. This could prove to be a fatal mistake, when India overtakes China this century as the country with the world’s largest population, and perhaps not long after this finally rises to join the ranks of the world powers in economic, political and military terms.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

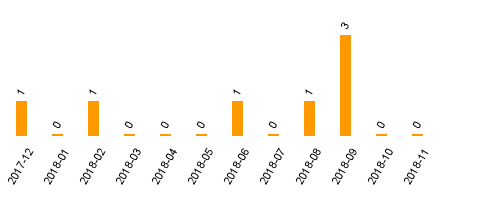

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)