"Natural Friends"? Relations between the United States and India after 2001

Müller, Harald ; Schmidt, AndreasDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (1.042 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2010/2157/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 87 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2009 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 25.08.2010 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/downloads/prif87.pdf (2009) |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.70 (Internationale Beziehungen: Allgemeines), 89.90 (Außenpolitik, Internationale Politik) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

Since the end of the Cold War, India has been very much in the ascendant, not only economically and technologically, but also from the military and political point of view. Many observers are therefore already talking about a world power of the 21st century emerging on the Indian sub-continent. It is not surprising, therefore, that India is playing an increasingly important role in the foreign and security policy considerations of the United States, the world’s only remaining superpower. Their respective size, power and geostrategic position mean that bilateral relations between the world’s most mighty and the world’s most populous democracy are a significant factor for the future world order. Central questions which are relevant for world politics are common positions with regard to the “war on terror”, on the one hand, and differences over the legitimacy of armed intervention in the sovereignty of other states, on the other. The long-term characteristics of their respective foreign and security policies are particularly noticeable in the attitude of the two states towards international law (in the context of war and peace), perhaps one of the most important instruments for protecting and shaping the global order. Despite common political values such as democracy, pluralism and rule of law, the relationship between the United States and India during the East-West conflict and in the following few years was characterized by alienation rather than friendship. India, which had had to struggle for its independence from Great Britain, looked on uneasily as the United States took on the legacy of the former colonial powers within the framework of its anti-communist foreign policy (for example in Vietnam) and supported coups to overthrow democratically elected governments in South and Central America. On the other hand, New Delhi’s reputation suffered significantly in Washington as a result of India’s role as a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement and its proximity to the socialist economic model of the former Soviet Union. The “thaw” did not begin until India started to gradually open up its economic system in the early nineties. Paradoxically, following initial U.S. sanctions, India’s nuclear tests in 1998 also prompted a positive re-assessment of India’s role in American foreign and security policy. From then onwards, the relationship improved noticeably and assumed a new strategic character following the events of 11 September 2001. India has been the target of terrorist aggression since it was founded in 1947. The biggest problem for New Delhi in the meantime is transnational Islamist terrorism. Anti- Indian, militant Islamic fundamentalism is nourished primarily by the continuing Indian- Pakistani conflict over the Kashmir region. This has led to three wars (1947/48, 1965, 1999) between the two neighbouring nuclear powers, also bringing them to the verge of nuclear war in 1990, 1999 and 2001/2002. It is not surprising therefore that India takes a keen interest in the fight against terrorism and in international cooperation which serves this goal. The attacks of 11 September 2001 suddenly provided India with an opportunity to close ranks with the world’s largest military power on the basis of converging interests. India offered the United States its full and unreserved support in the “war on terror” in an unprecedented declaration of solidarity. Shortly afterwards, U.S. President Bush and the Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee described in a joint declaration the common war on terror as the mainspring of their countries’ mutual relations. When the Indian sub-continent was hit by a new wave of terrorism from Pakistan in 2001/2002, the United States increasingly supported the Indian position and exercised tremendous political pressure on its ally Pakistan, despite the fact that it urgently needed Pakistan’s support in the fight against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. All things considered, the Indian Government’s decision to side with the United States in the fight against transnational terrorism can be regarded as a political success. For the first time, the United States described the elections in Jammu and Kashmir in autumn 2002 as “free and fair”, and called upon the Pakistani Government to put an end to transnational terrorism emanating from its territory. Moreover, the antiterrorism alliance, which was forged following the attacks of 11 September 2001 and was further consolidated in the course of the wave of terror in India in 2001/2002, prepared the ground for expanding bilateral relations between Washington and New Delhi in other fields. As a result, both states have not only expanded their trade relations spectacularly in recent years, but have also intensified their military cooperation. Furthermore, a recent nuclear agreement with the United States means that India has de facto officially been admitted to the club of nuclear weapons states. The so-called nuclear deal means that India now has access to the world’s nuclear market, a factor which is extremely important for the country’s energy supplies. The partnership with a thriving India is playing an increasingly important role in the United States’ “Grand Strategy”, particularly in the context of Washington’s competition for power with its challenger, China. Washington wants New Delhi to act as a counterbalance to China in Southern Asia in order to contain Beijing’s influence in the region. Many observers conclude that India and the United States are not merely strategic partners, but much rather “natural friends”: two democracies with the same opponents (China, Islamist terrorism), the same values, transnational networks and concurring economic interests. However, it would be overhasty to presuppose perfect harmony between Washington and New Delhi. Contrary to the hopes of policy-makers in Washington, India did not simply let itself become integrated in the United States’ foreign and security policy.

Kurzfassung auf Deutsch:

Auf den ersten Blick scheint nichts naheliegender zu sein als ein enges Bündnis zwischen den USA und Indien. Die mächtigste und die bevölkerungsreichste Demokratie der Welt verbinden dieselben Gegner (China, islamistischer Terrorismus), gleiche Werte und ähnliche wirtschaftliche Interessen. So zögerte Indien nach den Anschlägen vom 11. September 2001 nicht, den USA seine volle Unterstützung im Anti-Terror-Kampf zuzusagen. In der Folge intensivierten beide Länder ihre bilateralen Beziehungen auch auf anderen Gebieten. Perfekte Freundschaft? Harald Müller und Andreas Schmidt zeigen in ihrem Report die Grenzen dieser Freundschaft auf. Nach ihrer gründliche Analyse kommen sie zu dem Schluss, dass es beträchtliche Differenzen über die Gestaltung der internationalen Ordnung gibt. Anders als für die USA haben Völkerrecht und internationale Organisation für Indien unbedingte Priorität und gelten nicht als Behinderung, sondern als Stütze der eigenen Souveränität. So distanzierte sich Indien nachdrücklich vom Irak-Krieg der USA und zeigte damit deutlich, dass es nicht bereit ist, sich vorbehaltlos an die USA zu binden. Mit dieser Wertschätzung von Völkerrecht und Vereinten Nationen liegt Indien deutlich näher an der Politik Berlins als an der jüngeren Politik der USA und könnte damit in Zukunft auch für Deutschland ein interessanter Verbündeter werden, wenn es darum geht, sich gelegentlich gegen den großen Bruder in Washington durchzusetzen.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

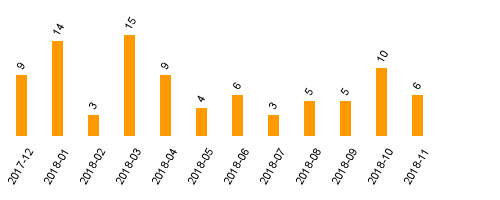

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)