Whither to, Obama? : U.S. democracy promotion after the Cold War

Poppe, Annika E.Download:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (368 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/3201/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 96 |

| ISBN: | 978-3-942532-07-5 |

| Sprache: | Deutsch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2010 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 23.10.2011 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/downloads/prif96.pdf (2010) |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | USA , Clinton, Bill , Bush, Georg W. , Obama, Barak , Außenpolitik , Demokratisierung |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.90 (Außenpolitik, Internationale Politik), 89.35 (Demokratie) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

When George W. Bush assumed office in January 2001, many pundits – some benevolently,others grudgingly – considered the new president’s main agenda to be as simple as ABC – Anything But Clinton. When President Barack Obama assumed office eight years later, many correspondingly described the latest president’s approach as ABB – Anything But Bush. The current U.S. president has inherited quite a number of difficult situations and crises from his predecessor that he has vowed to handle very differently: among others, the two unpopular wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the treatment of prisoners in Guantánamo and other, undisclosed locations, the global financial crisis, the relationship to Pakistan and Iran, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. This PRIF Report is concerned with how Obama handles one particularly tainted legacy of the Bush administration: the global promotion of democracy. Is Obama discarding his predecessor’s favorite but severely criticized project, is he keeping it with slight modifications, or is he taking a completely new approach? In order to answer this question, this PRIF Report turns to the larger context in which the Obama administration is operating. It first looks at how the idea of being an exceptional nation has shaped an exemplarist and an activist variant of democracy promotion, and portrays the current debate about this policy’s underlying rationales and its impact. It then assesses Obama’s immediate predecessors, Clinton and Bush, in terms of their democracy promotion policies and the rationales they have mustered in its favor. In light of these parameters that form the backdrop against which the Obama administration has to position itself, the current administration’s first initiatives regarding democracy promotion are assessed and interpreted with a view to this policy’s future. Obama, as this analysis shows, cannot and will not abandon democracy promotion altogether. Deeply engrained in the country’s national identity is the notion that the United States holds a special place and has a special role to play among the nations of the world. A central part of this American ‘exceptionalism’ is the ambition to liberate and enlighten the world by endowing it with human rights and democracy. That it is part of a genuine American mission to promote democracy abroad is fairly uncontroversial and no U.S. president can elude the issue. Controversies about how to promote democracy, however, have shaped the 20th century, especially the post-Cold War presidencies, and just as the controversy over means – quiet exemplarism or active (peaceful or military) intervention – the set of rationales for democracy promotion has developed and changed over time and remains a matter of considerable contention at the beginning of the 21st century. The analysis of rationales the Clinton and Bush administrations have drawn upon to legitimize the promotion of democracy shows that normative arguments play a very central role. Rationalist reasoning, however, is just as important: spreading democracy abroad, administration officials insist, makes the United States more secure, creates stable markets and opportunities for trade, provides other peoples with prosperity and security, and contributes to world peace. The Obama presidency, slow to develop its own democracy agenda and rhetoric, likewise draws upon normative motivations but is relatively silent when it comes to promoting democracy based on an agenda which pursues its own interests. This stands in especially sharp contrast to the Bush administrations, which had forcefully maintained that promoting democracy everywhere was a security imperative and did not shy away from accomplishing this aim through the use of military force, and which regularly employed Manichean language to underline the significance of democracy promotion as a foreign policy panacea. The Obama team has substantially scaled back the use of such grandiose rhetoric and has assumed a markedly more reserved stance on the issue. In many respects, as it takes its first steps on the issue the Obama administration resembles the Clinton presidency in how it handles the promotion of democracy. Democracy promotion under Obama seems once again to be considered one goal among others and is handled within a basically pragmatic foreign policy direction. Obama, like Clinton, favors a non-confrontational approach to democracy promotion, focusing on states that are inviting help from outside – and not primarily on rogue states as Bush did – and also decidedly favors multilateralism over unilateralism. Like both preceding presidencies, the Obama administration has raised the budget for democracy assistance and has affirmed repeatedly that it is committed to spreading democracy abroad as a responsibility the American people owe to the world. Whereas, overall, democracy promotion under Obama stands in the light of continuity rather than change, he is beginning to shape his own approach. Distancing himself from the two George W. Bush administrations, Obama has conceded the existence of previous U.S. mistakes and now emphasizes mutual understanding and the non-coercive character of democracy (promotion). His administration has also changed the status of democracy promotion from signature issue to embedding it along with human rights promotion as part of a broader development policy framework. Especially in contrast to the time during which the Clinton administrations were operating, the Obama team faces circumstances that have a discouraging effect on any ardent democracy promotion efforts: the democratic euphoria of the 1990s, fueled by the end of the Cold War and democracy’s ‘third wave’, has given way to a debate about its global backlash, while the United States is concerned with its own relative decline in light of new and aspiring rising powers on the world stage. As a consequence, Obama – in contrast to both his predecessors – draws heavily on the image of the U.S. as a ‘beacon’: promoting democracy by example. This may, in general, be the style he personally prefers; it is also fitting at a juncture where the U.S. lacks the resources and the credibility to promote democracy emphatically and on a large scale. Within this global context, Obama is careful not to have democracy promotion stand in the way of his agenda of global reengagement, fostering constructive relationships with all kinds of regimes and thus eliciting democratic change in the long run, a strategy strongly criticized by adherents of the Bush strategy. Whether he will be successful with his approach to democracy promotion within the foreign policy agenda remains to be seen.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

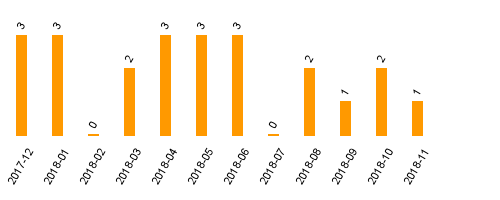

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)