From confrontation to integration : the evolution of ethnopolitics in the Baltic states

Aklaev, AiratDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (247 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2008/272/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 59 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2001 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 26.01.2008 |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | Baltikum , Integration , Minderheitenpolitik |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 15.73 (Baltische Republiken), 71.63 (Minderheitenproblem) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

This report focuses on two Baltic states – Estonia and Latvia – that have proved of particular concern to European policy-makers on account of the intense ethnopolitical tensions to which their policies on citizenship have given rise – tensions that reached crisis-point in 1993/94. The report argues that we are currently witnessing a new stage in ethnopolitical developments in the Baltics, shaped by a series of important new factors that emerged in the late 1990s. Those factors are: the stabilization of independent statehood; a relatively successful transition to functioning market-economies; the institutionalization of democratic political competition; the process of EU accession; and the re-emergence and development of civil-society institutions. In combination, these factors have tended to attenuate ethnopolitical attitudes and promote integrationist discourses which accord priority to inter-ethnic coexistence and constructive patterns of ethnic conflict management. Following the introduction provided in Chapter 1, Chapter 2 reviews the sources, patterns of manifestation, and evolution of ethnopolitical problems in Estonia and Latvia during the 1990s, and outlines the changes in the approaches used to resolve them. The entire dynamics of ethnic relations in Estonia and Latvia during the Soviet period was shaped by rapid and dramatic ethnodemographic changes, and by the creation of an ethnic divide between the Balts and the Russian-speaking migrants, manifested in language barrier, differences in occupational structure, distinct political orientations. This helped ensure that strict legislation on official languages (first adopted in the late 1980s) and exclusionist citizenship-policies won a high political profile when state independence was regained in 1991. Moreover, the simultaneous transition to democracy and independence has itself generated its own legacies, which, in their turn, have rendered post-communist ethnopolitics even more complex, superimposing the citizen/non-citizen divide onto the ethnic divisions. Since 1991, ethnopolitical developments in Estonia and Latvia have passed through three major stages. These are distinguishable by the changes that have occurred in the dynamics of ethnic conflict and in the approaches adopted to its management. The stages concerned are: 1) post-transitional confrontation resulting from the institutionalization of hegemonic control and ethnic dominance and entailing escalation to ethnopolitical crisis (August 1991–spring 1993 in Estonia, August 1991–spring 1994 in Latvia); 2) transition to de-escalation, a ‘wait-and-see’ period followed by exploration of alternative strategies of conflict management through political and societal integration (1994–early 1998 in Estonia, 1994–1999 in Latvia); 3) initial attenuation of ethnic tensions and start of conflict transformation in conjunction with implementation of integrationist strategies of ethnic peace-building (early 1998 onwards in Estonia, late 1999 onwards in Latvia). Chapter 3 outlines various crucial new factors that have helped shape contemporary Baltic ethnopolitics. With the stabilization of independent statehood, a feeling of security has been created among the Balts, and the integration of II Russian-speakers has come to be viewed as an increasingly sensible option. The proficient way in which the Baltic states have managed the transition to functioning market economies both serves as impressive proof of their determination to move away from the communist past and gives ground for optimism in regard to their future performance. At the same time, regions which, during the Soviet period, had been highly industrialized and had attracted Russian-speaking immigrants fell into a state of stagnation as a result of market reform, causing serious social dislocation. The institutionalization of democratic political competition has permitted the parties of the centre to gain the upper hand over the nationalist right. It also encouraged the adoption of a conciliatory and accommodating stance on ethnic policies as votes were sought among newly naturalized Russian-speaking citizens. The progress of naturalization has prepared the ground for the emergence and development of inter-ethnic political coalitions. European integration and the prospect of Baltic accession to the EU has moved to the forefront of both domestic and foreign policy. In their attempts to meet the requirements for EU membership, Baltic decision-makers have had to: take into account the European Commission’s recommendations on the issue of the resident Russian-speaking population; adhere to the norms of the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities; and accelerate naturalization procedures and the integration of Russianspeakers into their respective societies. The re-emergence of civil-society institutions and the gradual development of the third sector has produced a new set of actors on the ethnopolitical scene in Estonia and Latvia. Since the mid-1990s, NGOs have assumed a increasingly significant role in the processes whereby non- Estonians and non-Latvians are integrated into respective national societies. Their activities have included: efforts to improve intercultural dialogue and understanding; language-teaching for non-Balts; influencing public opinion to accept multiculturalism; and promoting patterns of civic, non-ethnically based, cooperation. Chapter 4 discusses the impact which new factors in Baltic political life have had on aspects of the ethnopolitical scene such as inter-ethnic attitudes and public discourses on ethnic issues. The chapter goes on to detail the results of recently conducted research into the various mindsets and motivations of different subgroups of political actors who share integrationist discourses at the state level (domestically centred pragmatists and European-oriented realists) and at the societal level (human-rights activists, civic partners, and minority-culture activists). It concludes by contrasting the conservative motives of those who propagate a ‘core nation’ discourse with the pragmatic and reciprocal-partnership motives that inspire those engaging in integrationist discourses. Pragmatic motives are to be found 1) at the state level, among holders of the utilitarian perspective, both in the European-realist and domestic-pragmatist subgroup, and 2) at the societal level, among holders of the multiculturalist perspective. The subgroups in question continue to perceive the conflict in interests among ethnic groups as acute but seek to change the pattern of inter-ethnic relations through orientation to superordinate, non-ethnic goals (such as realistically framed national-security interests, partypolitical expedience, or job – or even financial – opportunities for societal groups engaged in state-sponsored integration-activities). Such a position generally allows scope for inter-ethnic bargaining and compromise and, in some spheres, interethnic co-operation. Pluralist partnership motives may be observed 1) at the state III level, among holders of the modernizing/liberal perspective (the modernizer and liberal subgroups), and 2) at the societal level, among holders of human-rights and civic-partnership perspectives (the human-rights and civic-partner subgroups). These actors have developed an interest in transforming the structure of interethnic relations in order to realize, in the first instance, their mutual interest in the country’s long-term development (modernizers and liberals) or, in the second instance, some shared non-ethnic (civic) interest. All this prepares the ground for long-term peaceful co-operation between differing ethnic groups that perceive each other as civilized partners solving the same mutually important problem. Chapter 5 traces the implications that the knowledge obtained on attitudinal change and differences in discourse within subgroups of domestic political actors may have in helping European policy-makers to craft more effective policies for promoting sustainable ethnic peace (more effective in the sense that they take into account the specific mindsets and motivations of these subgroups). Previous Western policies designed to put pressure on the Baltic governments – which, in the early phase of re-independence, were dominated by right-wing nationalist coalitions – proved successful and produced major changes on the domestic ethnopolitical scene. Centrist coalitions which tend to espouse ethnopolitical moderation and adopt accommodating stances on ethnic issues have now come to the fore. Constructive policies aimed at the pluralist inclusion of non-Balts through state and societal integration have taken root and have replaced ethnonational exclusivism. Pressure to adhere to European standards in protecting minority rights should be maintained, in order to ensure the continued marginalization of radical nationalist groups and preclude the establishment of illiberal ‘ethnic democracies’ in eastern European countries seeking to form part of an enlarged EU. At the current stage of ethnopolitical development in the Baltics, when the influence of nationalist politicians on domestic politics is on the decline, new target-groups of political actors require the attention of European policy-makers. The institutions and instruments of preventive conflict-management should be reviewed and expanded accordingly. Policies of clear, systematic pressure on propagators of the ‘core nation’ discourse need to be supplemented with increased, prioritized support for political actors who engage in integrationist discourses. To be effective, such support not only needs to be tailored to the level (state or societal) at which the integrationists in question are operating; it also needs to take into account the differences in mindset and motive between the various subgroups within each of these levels.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

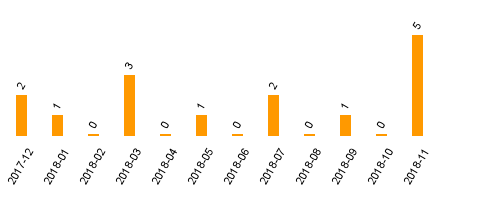

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)