Still a chance for negotiated peace : applying the lessons of the CSCE with a view to a Conference on Security and Co-operation in the Middle East

Groll, Götz vonDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (39 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2008/286/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | HSFK-Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung |

| Schriftenreihe: | PRIF reports |

| Bandnummer: | 45 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 1997 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 31.01.2008 |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | Konferenz über Sicherheit und Zusammenarbeit in Europa , Friedensverhandlung , Nahostkonflikt , Konfliktregelung |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.79 (Internationale Konflikte: Sonstiges), 89.77 (Rüstungspolitik), 89.73 (Europapolitik, Europäische Union) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

The recent election of Benjamin Netanjahu as the new prime minister of Israel has created apprehensions, particularly among the country's Arab neighbours, that the peace process in the Middle East could result in deadlock or even fail. First Arab reactions to the change in the political leadership have been characterised by a mistrust of Netanjahu and of his coalition government. However, both the summit meeting of the Arab League held on 22/23 June, 1996 and the diplomatic activities of leading Arab politicians have made it clear that those countries which have already concluded peace treaties with Israel have no wish to jeopardise them. Even Syria whose negotiations with Israel were suspended months ago does not seem to wish to exacerbate the situation. Against this background, Israel and Jordan are the countries which could have a key role to play: Bilaterally, their relations have already improved considerably on the basis of the peace treaty of 1994. But this treaty also contains a multilateral provision which still remains to be fulfilled: this is that both Parties have committed themselves to the creation of a Conference on Security and Co-operation in the Middle East (CSCME) along the lines of the Helsinki (CSCE) process. There is to date, however, no evidence of any activity on either side to im plement this part of the peace treaty. This Report examines the question as to whether or not it would make sense to create a CSCME in addition, or as an alternative to either the Madrid peace process which seems to stagger along tenaciously, or the Mediterranean conference, initiated by the European Union some months ago, which also involves part of the Middle East region. Since the authors of the Israeli-Jordan plan obviously had the 'success-model' of the CSCE in mind, this Report also looks at some of the basic factors and circumstances responsible for the success of the CSCE and tries to discover whether or not comparable conditions exist in the Middle East, particularly: · a geographical delimitation of the region that makes sense politically and ensures that all parties involved in conflicts in the region and necessary for their solution are included in the negotiations; · the presence of 'important' parties prepared to take the initiative in extending invitations, in sponsoring or moderating such negotiations; · the willingness of the parties involved in regional conflicts both to contribute to their solu tion without recourse to military action or other means of force (except for the purpose of self-defence) and to consider future developments 'open-mindedly' in the sense that fron tiers and zones of influence can be amended by peaceful means and by agreement; · a broad concept of 'security' which includes both co-operation as a means of achieving common security, and package deals to arrive at a balanced compensation of give and take; and finally · a willingness to embark on a lengthy process of compensation of interests, trust in the con fidence building quality of verifiable agreements and the healthy effect of implementation debates where alleged cases of non-implementation must be explained. Although all the conditions under which a possible CSCME would have to be organised are too intricate to justify their comparison with the European situation of the early seventies, the following criteria provide a useful framework for a debate: · today it is no longer possible to juxtapose the states of the Middle East against each other as antagonists of an East-West conflict, neither can these countries profit any more finan cially from such a confrontation. On the contrary: the global situation has developed in the opposite direction, manifesting a general tendency and willingness to help bring peace to the region, and even to pay for it; · one Middle East state appears to fulfil the main criteria required to extend an invitation to CSCME-consultations, namely Egypt. The country has the necessary political weight, dip lomatic relations with all of the potential participants, and has for many years actively pro moted the peace process; · although 'refraining from the threat or use of force' is not yet a principle applied by all par ties to conflicts in the region, it does at least figure in all declarations governing the relations of Israel with Egypt, Jordan and the Palestinian Council; · it is furthermore an open question whether the parties to a CSCME will comprehend, dur ing the multilateral negotiating process, that mutual and common security cannot be reached overnight: intermediate steps will first be required in order to build confidence; and that 'conventional thinking' can only be overcome by open debates on the implementation of, or the difficulties in implementing agreed measures. All of these are arguments in favour of a negotiated peace. This is the aim of the Madrid peace process which started in October 1991, and which was shaped after the CSCE model. The same is also true for the Mediterranean Conference, convened in Barcelona by the European Community in November 1995, in which a part of the Middle East region is represented. This Report tries to establish therefore why 'Madrid' has not so far become a synonym for success in the way 'Helsinki' did, and why Barcelona cannot replace a CSCME. The Madrid peace negotiations run along four bilateral tracks - those between Israel and the Palestinians, and with Jordan, the Lebanon and Syria; multilateral negotiations are held in five working groups, each addressing a specific subject and involving a great number of states of which only a few actually belong to the region. A comparison of these two levels of negotiation shows that the bilateral one is the more important of the two. When difficulties arise on a bilateral track, talks on the same subject then stagnate in the multilateral working group: the September 1993 Oslo agreement which in turn led to the Gaza-Jericho agreement, and the peace treaty between Israel and Jordan of October 1994 stimulated talks at the multilateral level. Thus, the structure of the Madrid peace process differs from that of the CSCE in two impor tant ways: in its focus on bilateral negotiations, and in the open-endedness of its multilateral negotiations in which an ever greater number of non-regional states and organisations partici pate. Each of these factors appears to have been detrimental to a smooth development of the process. The multilateral negotiations in particular suffer from repeated bouts of stagnation. Positive post-1993 results were due to progress in the bilateral negotiations between Israel and the PLO, and between Israel and Jordan. The Madrid process therefore can draw nearer the aims of its initiators only if there were to be progress in the negotiations between Israel and Syria, and between Israel and the Lebanon. Even then, however, the final aim of a compre hensive peace in the region still cannot be realised since two of its states are excluded: Iraq and Iran. The very fact that their present regimes are both notorious trouble-shooters and Is rael's arch-enemies should induce the initiators of a CSCME to bind them in into any lasting regional settlement. There is also reason to believe that the large number of outer-regional participants involved in the Madrid process is less than helpful from the point of view that their understanding of 'peace' only partly coincides with that of the states of the region; furthermore, they do not always play the role which the regional parties expect of them. The Barcelona Mediterranean Conference, on the other hand, is of very recent date and the measures it has so far contemplated - in particular preparations for a Free Trade Zone - carry a fulfilment deadline as far into the future as 2010. Nothing very definite can as yet be said about the success of this endeavour. One point, however, is quite clear: its main emphasis will be on economic co-operation, in particular with the Maghreb and much less with the Middle East region. Since both 'Madrid' and 'Barcelona' appear to have encountered difficulties in realising a comprehensive peace settlement for the Middle East, it does indeed seem worthwhile considering a new departure: to promote the idea of a 'Conference on Security and Co- operation in the Middle East'. The participants of this Conference ought to comprise the states of the 'central zone', i.e. Israel, its Arab neighbours and the Palestinian Council; the member-states of the Gulf Co- operation Council; and also those states which to varying degrees are involved in conflicts geographically located between the Mediterranean and the Persian-Arabian Gulf, i.e. Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Cyprus. The invitation should be based on one of the most important criteria which enabled the Europeans and North Americans to accept the Finnish invitation to the 'Helsinki Consultations': the participation of governments in the consultations and negotiations does not constitute a legal recognition of the existing political conditions in the region. All those states and organisations outside the Middle East region which have for years engaged themselves politically, militarily or economically in the area, such as the United States, the United Nations, the Russian Federation and the European Union, should play an important role in the process, but rather that of a moderator deprived of the right to vote, whilst other interested states such as Japan could be given observer status (as in the case of the OSCE) - to underline the character of a CSCME as a regional conference which places the interests of the parties directly concerned at the centre of its attention. It should in principle be possible to put all questions of security and co-operation which are of importance to the region, on the agenda of a CSCME. It seems, however, likely that agree ments can be reached more easily on some subject matters than on others. The parties to the Conference would therefore be well advised to start off with only five of the ten principles of the Helsinki Final Act, i.e. refraining from the threat or use of force, the peaceful settlement of disputes, non-intervention in internal affairs, co-operation among states and the fulfilment in good faith of obligations under international law. Such a catalogue commonly agreed between the participants of a CSCME would in itself already constitute a great success. · The principle 'Refraining from the threat or use of force' is part of the Charter of the United Nations and should be supported by all regional parties to the Conference, even by those which at present do not represent a state authority. · The principle 'Peaceful settlement of disputes' might induce Iran and Iraq - if invited to the Conference - to return to a system of international law to which they had already obliged themselves when joining the United Nations, since their participation in this Conference would put an end to their isolation. · The principle 'Non-intervention in internal affairs' is also a part of the UN Charter and fre quently invoked by Israel and its Arab neighbours. The last paragraph of this principle, as formulated in the Helsinki Final Act, is of particular interest under present Middle East conditions: The participants of the CSCE agreed that they will '...refrain from direct or indirect assistance to terrorist activities, or to subversive or other activities directed towards the violent overthrow of the regime of another participating State.' · The principle 'Co-operation among States' opens up possibilities for fields of interstate relations beyond the intricate security problems and the fundamental differences behind them, and provide participants with opportunities to better understanding and appreciation of the importance and usefulness of good neighbourly relations. · Finally, the principle 'Fulfilment in good faith of obligations under international law' - the Xth principle of the Helsinki Final Act - would seem to be suitable for inclusion in a Final Document of a first CSCME since all parties to conflicts in the Middle East consider it very important to fulfil acrimoniously any treaty once it has been concluded. On the other hand, the Conference could be blocked at an early stage if participants attempted during the first round of negotiations to agree on common formulae of controversial principles such as sovereign equality, inviolability of frontiers, territorial integrity and equal rights and self-determination of peoples, or similarly if they attempted to define together the meaning of human rights' criteria such as freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief. When embarking on an inter-cultural dialogue on human rights issues, participants must be very cautious. By no means ought this dialogue to be overshadowed by other topics nor should it be misused as negotiating fat to obtain better results in other fields. The criteria worked out by the 1990 CSCE Conference in Copenhagen on the subject of National Minorities could be studied with a view to their suitability for the settlement of inter-ethnic conflicts in the Middle-East. A CSCME would also be well advised, in the beginning, not to be too ambitious in terms of reducing military hardware and to content itself, like the CSCE, with a discussion of Confi dence Building Measures such as the prior notification of major military manoeuvres and the voluntary exchange of observers. Since the potential participants' interests in economic co-op eration seem to differ considerably, they would be well advised to start off by ending all forms of boycotts and similar restrictions. The facilitation of tourism across the border, family reunification, a better exchange of information, youth exchanges and other such steps might later culminate in a vast system of international arrangements such as the 'human dimension' of the CSCE/OSCE. *** The co-operation of the two authors of this Report stems from a lecture read by Götz von Groll on 13th March, 1996 entitled 'Can the lessons learned from the CSCE be helpful in set tling the conflicts in the Middle East?' which was part of the 6th spring academy of the PRIF on the subject: 'The Mediterranean - a zone of unrest' conducted by Berthold Meyer. Götz von Groll was the desk officer of Auswärtiges Amt co-ordinating the CSCE-policy of the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1971 to 1977. During these years, he participated in all CSCE consultations, the formulation of the CSCE-Final Act in Geneva as well as the Foreign Ministers and the Summit Conference in Helsinki 1973/75. In 1977, he was head of the Federal German Delegation for the preparation of the first CSCE Follow-up meeting in Belgrade. Berthold Meyer participated in the seventies in a number of international CSCE conferences of youth organisations, and directs, since 1981, PRIF's research on CSCE/OSCE, European security problems including European-Mediterranean relations.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

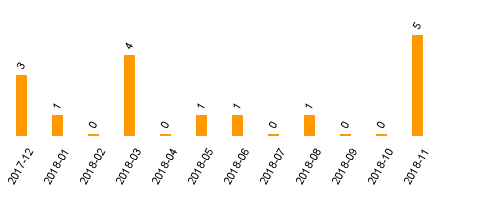

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)