Reforms in the EU’s aid architecture and management : The Commission is no longer the key problem : Let’s turn to the system

Grimm, SvenDownload:

pdf-Format: Dokument 1.pdf (1.236 KB)

| URL | http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/3292/ |

|---|---|

| Dokumentart: | Bericht / Forschungsbericht / Abhandlung |

| Institut: | DIE - Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik |

| Schriftenreihe: | Discussion paper // Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik |

| Bandnummer: | 2008, 11 |

| ISBN: | 978-3-88985-401-8 |

| Sprache: | Englisch |

| Erstellungsjahr: | 2008 |

| Publikationsdatum: | 14.08.2011 |

| Originalveröffentlichung: | http://www.die-gdi.de/CMS-Homepage/openwebcms3.nsf/(ynDK_contentByKey)/ANES-7GBHMM/$FILE/DP%2011.2008.pdf (2008) |

| SWD-Schlagwörter: | Europa , Entwicklungszusammenarbeit |

| DDC-Sachgruppe: | Politik |

| BK - Basisklassifikation: | 89.93 (Nord-Süd-Verhältnis), 89.73 (Europapolitik, Europäische Union) |

| Sondersammelgebiete: | 3.6 Politik und Friedensforschung |

Kurzfassung auf Englisch:

Aid effectiveness is an issue for all donors, including the EU as a system of 27 member states plus community organisations. As the European Commission has established itself as an international cooperation agency, it has increasingly been asked for evidence on the effectiveness of aid, possibly even more so than bilateral donors. Aid has been administered by the European Commission since 1958, yet the European institutions have only had a distinct mandate for development cooperation since the Maastricht Treaty of 1993. Since then – and also in the Lisbon Treaty – development cooperation has been a shared competency of the European Commission and member states. This paper examines European Commission policybut also assesses the system as a whole. Assessing the effects or potential outcomes of reforms requires substantial information. As a result of recent reforms in the European Commission’s aid administration, information about the EU’s aid system is now more readily available, not least due to the publication of the annual report on aid issued by EuropeAid. Other independent sources of information are also available, including Court of Auditor reports, DAC peer reviews and member state institutions’ enquiries. Furthermore, work by researchers on EU cooperation policy has increased. Financing from the EU accounts for more than half of global Official Development Assistance (ODA), of which one fifth is administered by the European Commission. Looking only at the Commission administered funds, the financing is based on two main sources: (a) funds from the EU budget and (b) funds beyond the EU budget (namely the European Development Fund – EDF). While this distinction has not changed, the structure of the EU’s budget for external actions (including development cooperation) has been modified. It has been simplified and includes four thematic instruments with (a) global coverage and (b) geographic coverage. At the global level, activities also fall under the funding responsibility of the Council (Common Foreign and Security Policy), while at geographic level the EDF persists. The international debate about aid effectiveness focuses on three main types of questions: should aid be scaled up substantially, will partner governments be required to improve their governance first, and what about donor governance (including issues of aid architecture)? These three strands also shape much of the debate around EU aid. Debates on the EU’s unsatisfactory performance in the past have addressed various aspects of the EU’s aid system. Despite a prioritisation among goals (poverty reduction has been identified as the main aim), there are persistent variations in the interpretation of this objective among member states. The organisational structure has changed and positive efforts have been made with the creation of EuropeAid and a move towards decentralisation to the Commission delegations in partner countries. Other reforms, however, like the geographical split between the Directorate-General on Development (Africa) and DG External Relations (rest of the world) are not yet complete. The Lisbon Treaty will address this issue, but not the remaining split in funding instruments with the European Development Fund (EDF) as a tool for cooperation with Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific separated from the general EU budget. However, since 2000, the EU has strengthened its overarching development cooperation strategy via the inclusion of new elements in the Cotonou Agreement and through the opment of the EU Africa Strategy and the European Consensus on Development. With regard to modalities of aid delivery, the EU has been subject to a number of critical assessments. Partly in response to these criticisms, innovative instruments such as budgetary support to partner countries have been created and the Commission now appears to be one of the leaders in international discussions. EU aid is targeting the political level more significantly and has included elements of quality control with regard to managing for results. Yet, within the broader scheme of the Paris Declaration, a first international assessment in 2006 revealed that much remains to be done. Challenges for EU cooperation architecture and management exist in at least four broader areas: First, the EU faces the challenge of increasing partner country orientation as demanded by the Paris Declaration. This includes the creation of an EU external action service, but also some organisational demands that come along with aid instruments like budget support and tronger political engagement at country level. Second, the EU still needs to grapple with how to organise a sensible division of labour in this com lex system in order to reduce double work and transaction costs for partners. The EU Code of Conduct on a division of labour is a promising start at policy formulation level. Implementation, however, will get to the core of some member states’ interests and will consequently be difficult. Thirdly, the EU faces a debate on what share of the budget should be spent on international development. A general budget review will be conducted starting in 2008. And strong lobby interests within the EU are likely to fight against even minor efforts towards reducing costs for the common agricultural policy to support increases in development assistance. If no increases are decided upon, the community-based funding for development will decrease against member state funding – i.e. not acting will result in shifting the aid architecture. And fourthly, pending reforms with the Lisbon treaty in the area of foreign policy will likely have effects on development policy. While the new not-so-called EU foreign minister will coordinate external relations more broadly (including development cooperation) and therefore be a step towards improving coherence, it is unclear whether this step will actually move the EU towards coherence for development. With the Commission having done most of its homework in development policy, attention should turn to systemic issues beyond communitarised development policy. Sorting out the system is a key task that the Commission and EU member states have yet to come to terms with. Some crucial decision will already be taken in 2008/09, determining the direction of EU development cooperation for the next decade or so.

Für Dokumente, die in elektronischer Form über Datenenetze angeboten werden, gilt uneingeschränkt das Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG). Insbesondere gilt:

Einzelne Vervielfältigungen, z.B. Kopien und Ausdrucke, dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden (Paragraph 53 Urheberrecht). Die Herstellung und Verbreitung von weiteren Reproduktionen ist nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Urhebers gestattet.

Der Benutzer ist für die Einhaltung der Rechtsvorschriften selbst verantwortlich und kann bei Mißbrauch haftbar gemacht werden.

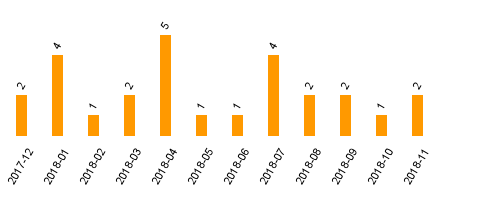

Zugriffsstatistik

(Anzahl Downloads)